By Kara Bue and Zack Cooper

The United States is losing ground in the Indo-Pacific region. Despite the Trump administration’s efforts to promote a “free and open” Indo-Pacific, regional trends are going against American interests. There is little reason to hope that these trends will reverse during the rest of the Trump administration. Instead, a new administration will be left to pick up the pieces.

Core Contradictions

The Trump administration’s central problem is that the President does not appear to support the strategy that his team has put forward. The National Security Strategy and the Defense Department’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report promote a regional approach based on strategic competition, strong alliances, economic prosperity, and shared values. But President Trump continues to undermine each of these elements.

President Trump has seldom embraced the “era of strategic competition” that his national security team has embraced. Instead, the President tends to speak positively about U.S. competitors, including Kim Jong Un, Vladimir Putin, and Xi Jinping. When asked whether he saw China as a “strategic competitor” – as it is labeled by his own National Security Strategy – Trump disagreed and said that he believed Beijing would be a “strategic partner.”

The Malabar 2019 Photo Exercise. (Source: The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command – Photo by Courtesy of JMSDF Public Affairs)

Meanwhile, the administration’s America First approach has damaged allied support for the United States. Many U.S. allies now see America as largely self-interested and unwilling to consider the interests of its allies and partners. President Trump often insists that U.S. allies should pay for the full costs of U.S. forces based on their territories, suggesting that the American military is a mercenary force. He also has publicly berated NATO allies for failing to pay their fair share. Far from building U.S. alliances to constrain strategic competitors, the result is a weakening of America’s alliances and leadership.

On the economic side, the Trump administration’s policies are just as confusing. President Trump remains focused on the current account balance, attacking China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and others for having trade surpluses with the United States. As a result, the administration has little in the way of a positive regional economic agenda. By cancelling the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the administration lost one of its most effective tools for both shaping Chinese economic behavior and bolstering economic activity across the Pacific.

Perhaps the area of greatest concern for many allies and partners is the erosion of U.S. support for common values. It is not simply that human rights have not been high on the administration’s agenda. The problems go deeper. President Trump has often appeared to go out of his way to undermine efforts to protect human rights. In Hong Kong, for example, President Trump suggested that this was an internal matter for Chinese leaders. And the administration has taken little action against major human rights violations, such as the Khashoggi case or the forced detention and mass “re-education” of at least a million Uighurs and other ethnic groups in Xinjiang.

These contradictions between the Trump administration’s professed strategy and the President’s own views are irreconcilable. Even the hardest working officials within the administration will struggle to overcome them, because they are fundamentally incompatible. As a result, the administration’s Indo-Pacific approach is unlikely to succeed writ large.

Even the most critical observers must acknowledge that there have been a few bright spots in the Trump administration’ s engagement in the Indo-Pacific. Ties with Vietnam have improved, as evidenced by the docking of an American aircraft carrier at Danang port. Relations with the Philippines are another positive due to the U.S. willingness to return the Balangiga Bells and to include the South China Sea within the area covered by the U.S. treaty commitment. The Trump administration has increased the attention paid to the Pacific Islands, particularly through more frequent senior level visits. Further, the Trump administration has sought to bolster its support of Taiwan. In July, President Tsai conducted an extended transit visit to the United States, which included a well-publicized stop in New York City – her first as President. That visit was shortly followed by the administration’s approval of a major USD 8 Journey of Freedom, Democracy, Sustainability in New York, 2019. (Source: Youth Daily News) billion arms sale package to Taiwan involving 66 new F-16C/D fighter aircraft. Progress in these four areas is commendable.

What do these issues generally have in common? President Trump is minimally interested or engaged in them, leaving his advisors more latitude to pursue their preferred policies.

As a result, his team has been able to implement elements of the stated Indo-Pacific strategy without significant interference from above. Elsewhere, however, President Trump is more engaged, and the results so far are negative.

Losing Ground in Asia

Aviation Ordnanceman 1st Class Don Salice explains damage control capabilities to Vietnamese officials in the hangar bay of USS Carl Vinson. (Source: The U.S. Navy)

In Northeast Asia, Japan and South Korea are at loggerheads. As a result, trilateral cooperation is becoming more difficult and China, North Korea, and Russia are seeking to drive a larger wedge between the U.S. allies. Meanwhile, U.S. leaders are assigning Tokyo and Seoul burdens of USD 9 billion and USD 5 billion, respectively, for hosting U.S. military forces. These cost sharing demands are likely to create anger in Japan and South Korea, while also serving as a distraction from building allied capabilities to meet shared threats.

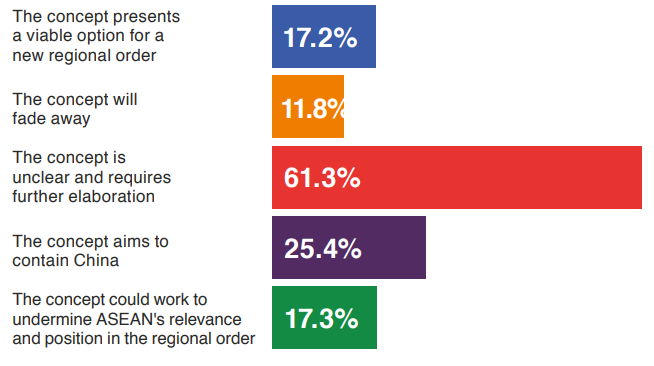

In Southeast Asia, there is little good news outside of Vietnam and the Philippines. Polls show limited support for the free and open Indo-Pacific strategy across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). One reason is that countries within ASEAN increasingly feel stuck between the United States and China. Facing a more powerful China and an inconsistent U.S., most countries in Southeast Asia are joining with Beijing or seeking autonomy, rather than aligning with Washington. Even Singapore has started to chafe publicly at the Trump administration’s approach, with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warning that Singaporeans are “anxious” about a “deeply divided and disgruntled” America.

Figure 1: How do you view the Indo-Pacific concept? (ISEAS Poll)

![]()

Elsewhere across the Indo-Pacific, the stories are similar. Indian leaders are frustrated with American economic actions. Australians are debating the pursuit of independent defense capabilities. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison refused to support placement of intermediate range missiles in Australia, which Secretary of Defense Mark Esper had suggested publicly before talking privately with his allied interlocutors. Thus, throughout the region, leaders are debating whether they can or should continue to rely on the United States.

Stuck in the Middle East and Afghanistan

Perhaps the area of greatest concern for many allies and partners is the erosion of U.S. support for common values.

To many Asian leaders, U.S. focus and forces still appear stuck in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Candidate and now President Trump argued for the end of the “endless wars” in the region, and this is perhaps the one area that Asia strategists tend to agree with the President. The National Security Strategy called for the United States to rededicate itself toward strategic competition with China and Russia, and to identify those countries as America’s top security concerns. This shift away from the Middle East and Afghanistan was similar to that promised by the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia, and remains supported by most observers in the Indo-Pacific region.

Here, however, the Trump administration’s inconsistencies have hamstrung its policies in the Indo-Pacific. President Trump remains engaged in discussions to forge a deal in Afghanistan, but the quick exit he had hoped for has yet to materialize. And the administration remains attached to an Iran policy that is sucking American time, attention, and forces back into the Middle East (as well as that of some U.S. allies). With limited increases in defense spending and an inability to prioritize among its regional commitments, the administration appears unlikely to commit more resources to the Indo-Pacific.

One example of this strategic distraction is the debate about deploying forces to the Persian Gulf to protect the sea lines of communication from Iranian interference. Although some in Washington are asking leaders in Tokyo, Canberra, and elsewhere to do more in the Indo-Pacific, U.S. requests are once again pulling them back into the Middle East. Given that China remains largely focused on Asia, the U.S. can hardly afford yet another distraction. And neither can its allies.

China, China, China

President Donald J. Trump unveils his new national security strategy during a speech in Washington in 2017. (Source: The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command)

Short-lived acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan said this year that his focus was “China, China, China.” But for all the administration’s tough talk, it has few results to show. Beijing has not agreed to stop its most problematic economic activities, including theft of intellectual property, restrictions on market access, unfair joint venture requirements, or massive state subsidies. Meanwhile, Beijing has engaged in repressive campaigns in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, increased pressure on Taiwan, and continued to expand China’s military posture through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

President Trump’s primary interest regarding China is decreasing the bilateral trade imbalance. But with the U.S. dollar strengthening as global market volatility increases, the U.S. trade deficit with China is going up, not down. Contrary to President Trump’s frequent promises, China has not increased purchases of U.S. agriculture and energy products. Meanwhile, tariffs by both sides are hurting consumers and slowing economic growth in the United States, China, and elsewhere.

President Trump’s approach could be summarized as talking loudly but carrying a small stick.

One U.S. observer has stated that the Trump administration’s approach is “confrontational but not competitive.” This is an accurate assessment. Too often the administration has threatened tough actions — against electronics companies such as ZTE and Huawei, for example — only to withdraw these threats under pressure from China. As a result, President Trump’s approach could be summarized as talking loudly but carrying a small stick. This strategy will not be sufficient to change the behavior of increasingly confident Chinese leaders. Nor will it make U.S. allies and partners more confident in the wisdom of supporting Washington’s approach.

What Comes Next?

Given all the challenges that the Trump administration faces in the Indo-Pacific, it is reasonable to ask what the next year (or five years) hold in store. Unfortunately, this assessment implies that the administration cannot escape its contradictions. President Trump’s views are not likely to evolve; and he is not the only cause of the dysfunction within the administration. As positions within the administration have turned over, they are increasingly filled by people who are more willing to tell the President what he wants to hear. This phenomenon appears to be getting worse, not better, as experienced leaders leave government.

Thus, the Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy appears destined to make little headway. The administration has succeeded in changing the debate on China. But it has failed to change Chinese behavior. It has failed to strengthen regional alliances. And it has also failed to build a shared consensus around the ultimate objective of its China policies. These tasks will likely fall to the next administration, whether that is in 2020 or 2024. The next team will have a tall task in front of them, one that they will have to accomplish in the face of diminished U.S. power and influence.

Kara Bue is a partner at Armitage International, L.C. Zack Cooper is a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.